In an age where digital connectivity forms the backbone of global commerce and communication, the possibility of a deliberate attack on the physical infrastructure enabling this connectivity represents one of the most concerning security scenarios for Western nations. The prospect of Russia severing the undersea internet cables between the United States and Europe has emerged as a particularly alarming threat—one with profound implications for the global economy and international stability. This report examines what would happen if Russia moved beyond testing and probing to executing a coordinated attack against the transatlantic cable network, analyzing the immediate economic fallout, long-term consequences, and potential responses to such an unprecedented disruption of global connectivity.

The Critical Undersea Infrastructure Landscape

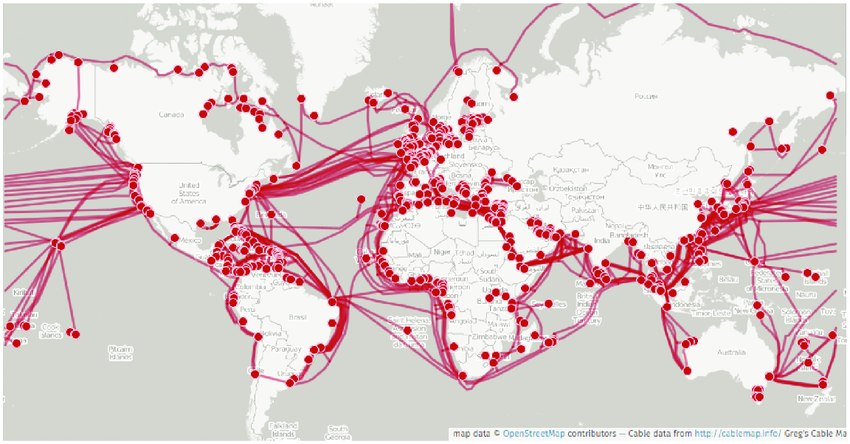

The digital world functions upon a surprisingly vulnerable physical foundation. Hundreds of fiber-optic cables, some no thicker than garden hoses, lie across ocean floors, enabling the near-instantaneous global data transmission we take for granted. These cables facilitate approximately 99% of international internet traffic, including phone calls, data transfers, and vital telecommunications essential to modern life4. The network spans about 745,000 miles globally, with particularly critical concentrations in the Atlantic Ocean connecting North America and Europe7.

While the first undersea telegraph cable was laid in 1858, today’s network consists of almost 400 submarine cables, most commercially owned and operated4. The transatlantic cables represent some of the most strategically important connections in this network, carrying massive volumes of data between the world’s largest economic blocs.

These cables aren’t just communication channels—they’re economic lifelines. Financial data moving through undersea cables enables approximately $10 trillion in daily financial transactions worldwide812. Major banking institutions, stock exchanges, and payment processors depend on this infrastructure to function properly. Central banks, large commercial and investment banks, and massive payment companies rely on these cables for transnational payments, foreign currency exchanges, and credit card processing7. Hedge funds and investment firms depend on this infrastructure for clearing and settling trades and for accessing the pricing and volume data they use to make investment decisions7.

Despite their critical importance, these cables remain surprisingly vulnerable. They lie exposed on the ocean floor, with their locations publicly documented due to licensing requirements11. The world’s critical undersea infrastructure is largely unguarded8, creating what security experts describe as an attractive target for adversaries seeking asymmetric ways to inflict damage on Western economies.

Russia’s Developing Capabilities and Strategic Intent

Evidence suggests that Russia has been systematically building capabilities to target undersea infrastructure. Western intelligence officials believe Russia’s efforts to monitor and potentially access undersea infrastructure are expanding, coordinated among various branches of the Russian military and security services, including the Russian Navy and the Main Directorate for Deep Sea Research (GUGI)8.

In recent years, Europe has witnessed a series of suspicious incidents involving damage to undersea cables, particularly in the Baltic Sea region. In December 2024, Finnish officials accused a Russian ship, the Eagle S, of deliberately dragging its anchor across the seabed to sever undersea cables in the Baltic Sea. They reported finding “dragging marks” extending for “dozens of kilometers…if not almost 100 kilometers”9, suggesting intentional action rather than accident. This vessel was identified as part of Russia’s “shadow fleet”—ships with uncertain ownership used to evade Western oil sanctions imposed over the war in Ukraine9.

This was just one in a pattern of suspicious incidents. In November 2024, two submarine telecommunication cables (the BCS East-West Interlink and C-Lion1) were disrupted in the Baltic Sea. The incidents occurred in close proximity and nearly simultaneously, prompting accusations of hybrid warfare10. In February 2025, Russia’s state-controlled telecoms giant Rostelecom reported that its underwater cable in the Baltic Sea had been damaged by an “external impact”5.

Former Russian President and close Putin ally Dmitry Medvedev heightened these concerns in 2023 when he openly declared that there were no longer any constraints “to prevent us from destroying the ocean floor cable communications of our enemies”8. This statement followed Western support for Ukraine and allegations regarding the Nord Stream pipeline explosions, suggesting potential retaliatory motivations.

Russia possesses the technical capabilities to target undersea cables at much greater depths than those found in the Baltic. According to reports, “Russia has carried out underwater military exercises at depths of more than 6,000 meters”12, which would be sufficient to reach most transatlantic cables. Its Directorate of Deep-Sea Research maintains a fleet of specialized ships and submarines designed for seabed operations12.

The Kremlin has consistently denied involvement in cable disruptions. When accused of sabotaging Baltic Sea cables, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov called the suggestions “ridiculous” and “absurd,” even suggesting Ukraine might be responsible instead14. However, the pattern of incidents and Russia’s documented interest in undersea infrastructure has kept suspicions focused on Moscow.

Immediate Economic Shockwaves

If Russia were to sever multiple transatlantic cables in a coordinated attack, the economic consequences would be swift and severe. The International Cable Protection Committee estimates that interruptions to underwater fiber optics communications systems have a financial impact exceeding $1.5 million per hour3. This figure likely understates the true cost of a major transatlantic disruption, which would affect the global financial system more broadly.

Financial Market Chaos

The first and most immediate impact would be on financial markets. High-frequency trading, which accounts for a significant portion of daily market volume, would be severely disrupted as it depends on millisecond-level transmission speeds between markets. The inability to execute cross-Atlantic trades at normal speeds would create price discrepancies between U.S. and European markets, leading to arbitrage opportunities that couldn’t be exploited due to the same connectivity issues.

Market liquidity would deteriorate rapidly as trading algorithms designed to function in a globally connected environment fail to operate properly. This could trigger circuit breakers on major exchanges as volatility spikes beyond normal parameters. Exchange data feeds between continents would be compromised, creating information asymmetries and potentially leading to panic selling in markets most affected by information gaps.

Banking System Disruptions

The global banking system would face severe operational challenges. Undersea cables handle trillions of dollars of transactions daily and help sustain the global banking industry3. A disruption would impede cross-border payments, foreign exchange operations, and correspondent banking relationships between U.S. and European financial institutions.

Major payment processing networks rely on continuous connectivity between data centers in North America and Europe. Disruption would impair credit card processing, international transfers, and settlement systems. While some redundancy exists in these systems, the volume of transactions that would need rerouting would create significant bottlenecks and delays.

The SWIFT network, which facilitates most international interbank messages, would face substantial operational challenges. While SWIFT has built in some redundancy, a major disruption of transatlantic cables would stress the system beyond normal parameters, potentially delaying critical financial communications.

Corporate Operations Impact

Multinational corporations with operations spanning both continents would experience significant operational difficulties. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems that rely on synchronized data between global locations would face synchronization issues. Cloud computing services, which rely on constant data exchange between global data centers, would see performance degradation for applications hosted on affected infrastructure7.

Customer service operations would be compromised for companies using international call centers or cloud-based customer relationship management systems. Revenue operations such as billing, collections, and accounts receivable functions that require cross-Atlantic data exchange would face delays and disruptions.

The severity of these immediate impacts would depend on several factors:

- Number of cables affected

- Duration of the disruption

- Location of the cuts (whether they affect primary or redundant pathways)

- Time required for repair operations

Cascading Economic Effects

Beyond the immediate impacts, a sustained disruption of transatlantic cables would trigger cascading economic effects across multiple sectors, extending well beyond the initial financial shock.

Supply Chain Breakdown

The global supply chain, already strained by recent disruptions, would face new challenges. Many logistics operations depend on real-time data exchange between continents. Shipping companies, airlines, and freight forwarders rely on continuous data connections to track cargo, manage inventory, and coordinate deliveries. Disruption of these systems would introduce delays and inefficiencies throughout the supply chain.

Just-in-time manufacturing systems that depend on constant communication between suppliers and manufacturers across the Atlantic would be particularly vulnerable. Production schedules would be disrupted as inventory management systems lose synchronization, potentially leading to production slowdowns or stoppages in manufacturing sectors with complex international supply chains.

Ports and shipping terminals rely on digital systems to coordinate loading, unloading, and customs clearance. Disruption of these systems would create bottlenecks at major ports, with potential ripple effects throughout global shipping routes. The impact would be particularly severe for time-sensitive cargo such as perishable goods and medical supplies.

Industry-Specific Impacts

Different industries would experience varying degrees of impact based on their reliance on transatlantic data flows:

Financial Services: Beyond the immediate market disruptions, longer-term impacts on financial services would be profound. Asset management firms with global operations would struggle to maintain accurate portfolio valuations as data feeds become unreliable. Insurance and reinsurance companies, which spread risk globally, would face challenges in risk assessment and claims processing for international policies7.

Healthcare and Pharmaceuticals: The healthcare industry increasingly relies on cross-border data sharing for research, telemedicine, and pharmaceutical supply chains. Clinical trials conducted across multiple countries would face data collection and monitoring difficulties. Telemedicine services connecting specialists across continents would be degraded. Pharmaceutical manufacturing and distribution, which require coordination between global facilities, would experience disruptions in production scheduling and inventory management.

Energy Markets: Energy trading platforms that facilitate the buying and selling of oil, gas, and electricity across the Atlantic would face operational difficulties. Price discovery mechanisms would be compromised, potentially leading to increased volatility in energy markets. Coordination of international energy flows, particularly important for European energy security, would become more challenging.

Technology Sector: Technology companies with distributed development teams would struggle to collaborate effectively. Software development processes that rely on continuous integration and deployment across global development centers would be disrupted. Cloud service providers would face challenges in maintaining data consistency across geographically distributed data centers, potentially leading to service degradation for their customers7.

Market Psychology and Investment Impact

Beyond the direct operational impacts, the psychological effect on markets could be equally damaging. Investor confidence would be severely shaken by such a demonstrable vulnerability in critical infrastructure. The perception of increased geopolitical risk would likely trigger a flight to safety, with capital flowing into traditional safe-haven assets such as gold, the US dollar, and government bonds.

Corporate investment decisions would be influenced by the new risk environment. Companies might delay or cancel cross-border investments due to increased uncertainty about digital connectivity reliability. This could have long-term implications for economic growth and productivity, particularly in sectors heavily dependent on digital infrastructure.

The insurance market for political risk and cyber risk would face a significant reassessment. Premiums for coverage related to infrastructure disruption would likely increase substantially, adding to operating costs for businesses with international exposure.

Alternative Routing Limitations

While some traffic could be rerouted through alternative pathways—such as cables connecting through other regions or satellite communications—these alternatives have significant limitations.

Satellite communications provide far less bandwidth than fiber-optic cables and experience higher latency, making them unsuitable for many financial applications and real-time services. The total capacity of satellite communications represents only a tiny fraction of the bandwidth provided by undersea cables, meaning they could handle only a small portion of displaced traffic.

Alternative cable routes would quickly become congested as traffic is redirected, creating bottlenecks and degraded performance across the global internet. Cables through the Middle East or around Africa could absorb some traffic, but these paths would introduce additional latency and would quickly reach capacity limits.

Past incidents provide some insight into potential impacts. When an earthquake near Taiwan damaged multiple cables in December 2006, it took 11 repair ships 49 days to restore service. The disruption affected internet links, financial markets, banking, airline bookings, and general communications across multiple Asian countries3. A coordinated attack could potentially create even more extensive damage than a natural disaster, particularly if designed to target the most critical connection points.

Repair Challenges and Timeline

Restoring connectivity after a major cable disruption presents significant challenges. Repairing undersea cables is a complex, time-consuming process that requires specialized ships and equipment. When cables are damaged, the first step is to precisely locate the damage, which can be challenging in deep ocean waters. Once located, a specialized cable repair ship must be dispatched to the area, which can take days or even weeks depending on the location and availability of repair vessels.

The actual repair process involves retrieving the damaged section of cable from the ocean floor, cutting out the damaged portion, splicing in a new section, and then carefully lowering the repaired cable back to the seabed. In deep waters or challenging weather conditions, these operations become even more difficult and time-consuming.

A coordinated attack specifically designed to maximize disruption could potentially target locations that are particularly difficult to access or repair, extending the outage period. Furthermore, if Russia were to actively interfere with repair operations—for example, by maintaining a naval presence near the damaged cables or engaging in electronic warfare to disrupt repair ship navigation—the restoration timeline could be extended even further.

Geopolitical and Security Dimensions

A Russian attack on transatlantic cables would represent a major escalation in international tensions, likely triggering significant responses from NATO and affected countries.

NATO has already begun to recognize the strategic importance of undersea infrastructure protection. In January 2025, NATO countries launched a patrol mission called “Baltic Sentry” to protect critical underwater infrastructure, deploying aircraft, frigates, submarines, and drones5. A direct attack on transatlantic cables would likely prompt an expanded version of such protective operations across the Atlantic.

The legal status of such an attack remains somewhat ambiguous under international law. While cutting cables during wartime would clearly constitute a hostile act, the status of such actions during peacetime is less clear-cut. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea provides some protections for submarine cables, but enforcement mechanisms are limited, especially in international waters12.

An attack of this magnitude would almost certainly be considered an act of hybrid warfare, potentially triggering Article 5 of the NATO treaty if attributed to Russia with high confidence. At minimum, it would result in severe diplomatic consequences and likely additional economic sanctions against Russia.

Building Resilience: Mitigation Strategies

In the face of this threat, Western governments and private companies have been working to enhance the resilience of undersea cable networks.

Current protection measures include increased naval patrols near critical infrastructure, enhanced monitoring systems to detect suspicious vessel activity, and improved coordination between military and civilian agencies responsible for infrastructure protection. NATO now has an undersea infrastructure coordination group that brings together military and civilian officials and can convene representatives from the private sector11.

For the financial sector specifically, resilience strategies include:

- Developing backup communication systems for critical functions

- Building redundancy into transaction processing systems

- Creating contingency plans for operating with degraded connectivity

- Establishing alternate routing agreements with telecommunications providers

- Conducting regular stress tests for connectivity disruption scenarios

Policy recommendations for improving overall resilience include:

- Strengthening international legal frameworks protecting undersea infrastructure

- Enhancing attribution capabilities to identify responsible parties for cable disruptions

- Developing clear deterrence strategies to dissuade potential attackers

- Investing in research for more resilient undersea cable designs

- Creating international standards for cable protection and repair

Conclusion: A New Economic Vulnerability

A Russian attack severing transatlantic internet cables would represent a watershed moment in modern conflict—demonstrating both the vulnerability of critical infrastructure and the changing nature of warfare in the digital age. The economic consequences would be immediate and severe, affecting financial markets, banking operations, supply chains, and countless businesses that depend on reliable transatlantic data connections.

The $10 trillion in daily financial transactions that flow through these cables7812 represent not just numbers on screens but the lifeblood of the modern global economy. Disrupting this flow, even temporarily, would create economic shockwaves that would reverberate throughout the global financial system. While some redundancy exists, the scale of disruption from a coordinated attack would overwhelm existing alternatives, creating economic damage measured in billions of dollars.

Perhaps more concerning than the immediate effects would be the precedent such an attack would set. It would signal a dramatic escalation in the willingness of state actors to target civilian infrastructure and could herald a new era of hybrid conflict focused on economic targets rather than traditional military objectives.

As digital dependency continues to grow, the vulnerability created by reliance on physical infrastructure like undersea cables will remain a strategic concern for Western nations. Addressing this vulnerability requires not just technical solutions but diplomatic, legal, and military approaches to deter attacks and enhance resilience. In an interconnected world, the security of the physical links enabling digital connectivity demands far greater attention than it has historically received. The economic stability of the global system may depend on it.